Tuesday, October 13, 2009

THE CATAWBA INDIANS:

"PEOPLE OF THE RIVER"

(updated 09/20/07)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center; do not use or duplicate in any way

| This unsigned 13-inch-tall "Rebecca Pitcher" (right) from the Hilton Pond Center's collection was made by a gifted Catawba Indian potter (name not known). It shows distinctive mottling--in this case, tan and black--typical of the tribe's clay artwork. Catawba pottery-making is practiced today by accomplished master potters who are training a new generation to form these beautiful creations from Piedmont river clay. |

|

Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History near York, South Carolina, lies just 15 miles from the Catawba River, so it seems likely our property was traversed in times past by Catawba Indians exploring its tributaries. Although this is pure speculation, there can be no doubt about the tribe's connection with the actual waterway, for the Catawbas call themselves yeh is-WAH h'reh, or "People of the River." Since water from Hilton Pond flows into Fishing Creek and eventually into the Catawba River, we feel a real affinity for the Catawba Indian Nation.

The Catawbas settled on the banks of the Catawba River--primarily in what is now York County, South Carolina--and built permanent, bark-covered roundhouses in which to live, plus huge Council Houses for tribal meetings. They hunted Piedmont woodlands and prairies and fished in the river and its feeder streams. They also farmed and planted corn extensively in the rich river bottomlands. Once a large and powerful group numbering in the tens of thousands, they waged ongoing war with the Cherokees and tribes of the Ohio River Valley, being successful in battles with the former but not faring well against the Six Nations. Hernando de Soto, the Spanish explorer, made first contact with the Catawbas in 1540. When Europeans began settling in the Carolina Piedmont, the Catawbas remained friendly, but many succumbed over the years to "white man" diseases such as smallpox; by 1826 there were only about 110 true Catawbas left, and some of those moved elsewhere.

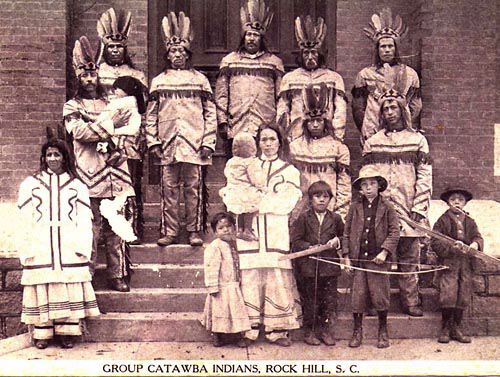

Catawba Indians at the Corn Expostion (Columbia SC, 1913)

In years since, the Catawba population has stabilized and grown, and there has been a resurgence of interest in Catawba heritage. Although there are no longer any full-blooded Catawbas, much of the tribe's cultural history has been retained by 2,000 or so descendants now living on or near the current reservation at Rock Hill SC.  (Sallie Brown Gordon, the last native speaker of the Catawba language--a dialect of Eastern Siouxan--died in 1952.) The tribe is also interested in preserving and conserving natural aspects of the reservation, especially habitats along the Catawba River bottomland. (Unfortunately, disagreements among various factions of modern-day Catawbas have resulted in lack of unity within the tribe; the public often hears of this turmoil rather than the good work of many tribal members.)

(Sallie Brown Gordon, the last native speaker of the Catawba language--a dialect of Eastern Siouxan--died in 1952.) The tribe is also interested in preserving and conserving natural aspects of the reservation, especially habitats along the Catawba River bottomland. (Unfortunately, disagreements among various factions of modern-day Catawbas have resulted in lack of unity within the tribe; the public often hears of this turmoil rather than the good work of many tribal members.)

Historically, a male Catawba's typical ceremonial garb consisted of a long-sleeved leather coat with fringe; long trousers; and a distinctive headdress made of a head band with large, erect feathers. Women wore a decorated coat, leggings, and a long skirt. (See photos of Benjamin P. Harris, above right, and a group of Catawbas at the S.C. Corn Exposition in 1913, above.) In modern times, some Catawba males have elected to wear Plains Indians war bonnets and turquoise jewelry, unfortunately propagating to students and the public the stereotype that all tribes and nations dressed alike.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center; do not use or duplicate in any way

CATAWBA INDIAN POTTERY

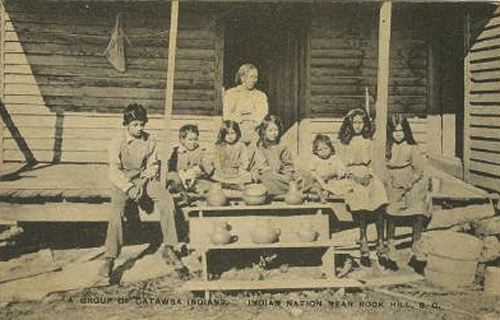

Perhaps the Catawba Indian Nation's greatest legacy is its pottery, made in simple, elegant style that is instantly recognizable. Production and sale of pottery is not a "new" phenomenon, as indicated by a circa 1910 postcard (above) depicting a Catawba family showing their wares. (Note that everyone pictured is wearing "white man" clothing quite unlike traditional Catawba garb.)

Large Chief's Head Pot

(11" x 9"; signed by Sara Ayers, undated; head detail below right)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center; do not use or duplicate in any way

In his book on The Catawbas, James H. Merrell states: "The Catawba women who continue to make pottery using the traditional techniques are an ongoing link with the tribe's past. They ensure that Catawba pottery will remain the oldest art form still produced in South Carolina."

Traditionally--and today--Catawba men and children still dig clay from pits along the Catawba River, often from prime sites kept secret from outsiders.  After cleaning the clay, Catawba women grind it into very fine powder to eliminate any gritiness from the final product. Water is added, and the mixture is worked to the proper consistency.

After cleaning the clay, Catawba women grind it into very fine powder to eliminate any gritiness from the final product. Water is added, and the mixture is worked to the proper consistency.

Unlike many modern potters who "throw" pots on a wheel, Catawbas use lumps or snake-like coils of clay to form their pots. After flattening a lump to make the pot's bottom, the potter joins the ends of a first coil and adds it to the base. All joints are smoothed, a second coil is added atop the first, then a third, and so on until the desired height is reached. This "green" pot is allowed to dry for a few days, after which the potter thins the walls and smooths inner and outer surfaces using tools that may have been passed down from her mother or grandma or great granny. These implements--made of bone, shell, wood, or metal--are among the potter's most cherished possessions.

Two Small Pitchers and a Small Vase

(Left: 6.5" x 3.5"; signed by Viola Robbins, 1995)

(Center: 3.5" x 1.75"; unsigned & undated)

(Right: 4.25" x 4"; signed by Sara Ayers, undated)

A final dampening of the pot allows the potter to polish it to a glass-like finish. Ornamentation may be added in the form of handles, spouts, or the head of ancient Chief Hagler or Nopkehe (see three photos just above), or as artistic incising on the outer surface of the pot (see small pot below left); Catawba Indian pottery is NEVER painted, nor is it glazed. (NOTE: Catawba INDIAN pottery should not be confused with Catawba VALLEY pottery from North Carolina; the latter is NOT Native American artwork.)

Three Small Containers

(Left: 2.75" x 2.5"; signed by Warren B. Sanders, 5/13/1996)

(Center: 4" x 2.5"; signed by Viola Robbins, 1995)

(Right: 2.75" x 3"; unsigned & undated)

Most potters sun-dry their pots before firing them outdoors in a pit or open fireplace, which--depending on how and where wood is placed on or in it during the process--produces a unique mottled pattern (see photo just above) of black, tan, orange, and/or or brown that makes the smooth but unglazed final product so distinctive. This technique is believed to have been used by the Catawbas for up to 4,500 years and apparently pre-dates more familiar pottery-making by tribes in the Southwestern U.S.

Large Horse Bowl

(12" x 6"; signed by Earl Robbins, 1990)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center; do not use or duplicate in any way

Perhaps the best-known Catawba potter in recent years was Sara Ayers (1919-2002), whose signed art is some of the most avidly sought by collectors. Among the more creative and accomplished of 20th century Catawba artists were Mildred Blue (1922-1997), Nola Campbell (b. 1918), and Georgia Harris (1905-1997). Catherine Canty (b. 1917) and Evelyn George (b. 1914) are also among the modern-era master potters, and--now that a few men have taken up the tradition--so is still-active Earl Robbins (b. 1922; see his very unusual "horse bowl" design above). For more information about these seven master potters and their work, visit the Web site for the Catawba Culture Preservation Project or click on their names above. There's also a new site created by Friends of the Catawbas.

The clay-working tradition of the Catawba Indian Nation is being continued by a new generation of artisans, many of whom are children or grandchildren of the folks listed above. Some are on their way to becoming master potters in their own right. The "new generation" of potters includes, among others, such Catawbans as Monty Branham, Keith Brown, Edwin Campbell, Donald Harris, Billie Anne McKellar, Della Oxendine, Elizabeth Plyler, Brian Sanders, Caroleen Sanders, Cheryl Harris Sanders, Freddie Sanders, Marcus Sanders, and Margaret Tucker.

NOTE: All Catawba Indian pottery pieces shown on this page are from the collection of Susan B. Hilton and on permanent loan to Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History; we thank her for her willingness to share this resource. Please contact us at FUNDING if you are interested in donating Catawba pottery or providing funds to help expand the Center's collection. Our pottery ranges in age from very recent to a few items that are nearly a century old; most are unsigned.

The greenish tint on many of the pieces depicted here is an artifact--the result of taking our photos outdoors under a canopy of green trees. Most Catawba pottery is semi-shiny gray-black, plus the other highight colors.

Please scroll down for photos of other items in the Center's collection. (Check back later as we add descriptions and images for new pieces.)

Incised Two-spout Pitcher

(6.5" x 3.5"; unsigned & undated)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center; do not use or duplicate in any way

Three Small Pitchers

(Left: 5.5" x 3.25"; unsigned & undated)

(Center: 4" x 2.5"; unsigned & undated)

(Right: 4.75" x 2.75"; signed but illegible, undated)

Two-necked Round Vase

(5.75" x 5"; signed by Viola Robbins, 1997)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center; do not use or duplicate in any way

Two Small Pitchers

(Left: 6" x 4.75"; signed by Florence Wade, 1993)

(Right: 4.5" x 3.75"; signed "Catawba Indian" & undated)

Three Small Pieces

(Left: Bowl inscribed with leaves; 2.5" x 2.75"; signed by Kimberly Ann Page, 1996)

(Center: Bowl with scalloped lip; unsigned & undated, but at least 65 years old)

(Right: Symmetrical vase; signed "Catawba Indian" & undated)

Four-hole Bowl Pipe

(Reeds were placed in each of the four side holes and the smoke mixture was placed in the center of the bowl; 5" x 4"; unsigned & undated)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center; do not use or duplicate in any way

Basket Stand

(6.75" x 3.5"; signed by Catawba potter Reola Harris 1921-1991, well-known for animal effigies and the twin sister of Viola Robbins; Reola began signing pottery in about 1979, so this piece likely dates to the late 1970s or 1980s)

Two Small Bowls

(Left: 6" x 3"; unsigned & undated)

(Right: 3.5" x 2.75"; unsigned & undated, but a well-worn piece probably almost a century old)

Large Arrowhead Pipe

(5" x 2.5"; signed by Earl Robbins, 1991)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center; do not use or duplicate in any way

OTHER CATAWBA INDIAN INFORMATION

The Blacksnake in Catawba Indian Art and Culture

by Thomas J. Blumer, Ph.D

Blumer, T. J. 1987. Bibliography of the Catawba. Scarecrow Press, Metuchen NJ, 547 pp.

Blumer, T. J. 2003. Catawba Indian Pottery: The Survival of a Folk Tradition. Univ. Alabama Press, 240 pp.

Blumer, T. J. 2004. The Catawba Indian Nation of the Carolinas. Arcadia Publ., South Carolina, 128 pp.

Bradford, W. R. 1946. The Catawba Indians of South Carolina. South Carolina Dept. Educ., Columbia, 31 pp.

Brown, D. S. 1966. The Catawba Indians: People of the River. Univ. South Carolina Press, Columbia, 400 pp.

Hudson, C. M. 1970. The Catawba Nation. Univ. Georgia Monographs #18, Athens, 142 pp.

Merrell, J. H. 1989. The Catawba. Chelsea House Publishers, Philadelphia, 112 pp.

Merrell, J. H. 1989. The Indians' New World: Catawbas and Their Neighbors from European Contact Through the Era of Removal. Univ. North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 400 pp.

Scaife, H. L. 1896. History and Condition of the Catawba Indians of South Carolina. Office if Indian Rights Assn., Philadelphia.

Speck, FG. 1969. Catawba Texts. Reprinted by AMS Press, New York, 91 pp.